Today, I’d like to outline and detail the workflow involved in making a video for Rhystic Studies. There are two reasons for this. The primary is that I want to encourage others to create something of their calling, and maybe seeing my process will inspire a new pathway in their own work. The secondary is that I want to better understand, for myself, what goes into baking this proverbial pie.

Importantly, I’m disinterested in “patting myself on the back” for all the effort behind these projects – I’ve said before that nobody cares how hard you work. We all work hard. Hard work is only one ingredient, and it’s accessible to everyone, and I believe in everyone’s ability to reach for that salt shaker when the water starts boiling.

Phase One: Research and Ideation

In my first semester of graduate school, I was advised to follow those brief moments of suspicion that arise when researching texts. It was framed to me as follows: whenever you suddenly pause from reading, and you look up from your book, and you think “huh…that’s weird” – take note. Something alchemical is happening there. Most of my term papers throughout the Ph.D. started with mild eureka visions like this.

Pay attention to what you find weird.

Most Rhystic Studies projects begin by asking very simple questions. The more basic, the better. “How is a foil Magic card made?” “Who designed the first Lantern control deck?” “How do you read Phyrexian?” Find the most reductive question you can ask about your topic and propose that out loud to yourself. Then, provide an answer in ten words or less. If you can’t, then you may be on to something. I find I’m more intrinsically motivated to pursue video topics that I know nothing about.

Having a broad sense of your research subject is important in this phase. Some topics are not deep enough to warrant an entire video. Some topics are too deep, and the scale is beyond the variable constraints (be them time, money, skill level, human resources, or whatever else.) Developing this sensibility comes with time. The longer you spend in your field, the better you will become at differentiating between small, medium, and large-scale projects. By now, I know which topics I can reasonably tackle in the 6-week window I’ve allotted myself to producing these videos.

Research is not linear. Research is iterative. The answer to every simple question often produces ten new questions, and ten more answers, and ten new questions to those answers, and so on. The project that starts at A never ends at B. C shows up and points you toward D, E appears in the digression, and actually your real thesis materializes somewhere around L-M-N-O-P. Embracing the uncertainty of this phase is fundamental. You must allow yourself to be set adrift. Fighting the current is antithetical to learning.

Something else: I stay away from Magic-related media during ideation. There’s much to be said about drawing influence from unrelated disciplines and expressions of art; I’ve found that my best ideas have always shown up when I’m not looking at cards. The Red Deck Wins video comes to mind – I was watching Wayne Fredrickson’s tattoo channel and listening to a lot of PUP, and the band’s name of course reminded me of Jackal Pup, and I wondered why that card was so memorable, and I asked myself, “under what circumstances would it be advantageous to run a creature that does a lot of damage to you? That’s weird…”

Toward the end of this phase, I begin contacting potential guests to interview and scheduling Zoom calls.

What I prioritize in this phase: curiosity, gathering sources, freeform thinking, macro reading, meandering the web, uncertainty

What I ignore: editorializing, making value judgments, personal bias, hyper-fixation, decision-making, projecting a desired end result

Phase Two: Notes Review, Guest Interviews, and Synthesis

After I’ve exhausted all my sources and pursued the visible rabbit holes (within reason), I begin the push-and-pull process of synthesizing my notes and developing my story. Most of this happens away from the computer. I go on long runs and think and plot. I let my mind chew through all the ideas. Downtime is invaluable for this phase. I’ve played guitar my whole life, and any time I learn a new song, I sleep on it and rehearse it the next day. Without fail, everything clicks after that brief period of rest. Something magical takes shape in the plasticity of the brain when you let new information settle in. I’m sure the phenomenon has been explained in science.

For interviews, I prepare ten, concrete topics to explore with my guests. I send the questions with plenty of time in advance. They are thorough and specific to the guest’s expertise and perspective. I insist that the guest speak the entire time, and I remove myself as much as possible from their responses. I record the conversation and listen back at least three times in full to be acutely familiar with everything discussed. I take timestamped notes to reference when writing the script.

Do you remember those Magic Eye books we loved as kids? The ones where, only by lazily staring at an illusion, a shape would emerge from the visual noise? Finding the narrative hook for a story feels a lot like that. You have a bunch of disparate information, and it is your job to trace the connective tissue that moves through it. Something about Neo seeing the Matrix and all that.

Rhystic Studies is decidedly not a platform for listicles. My videos are not book reports. I am not simply regurgitating all the inputs from phase one into a longform video. I am not plugging and playing – there is no worksheet to this. Rather, I am humanizing the factoids, and providing historical context, and towing the line between education and entertainment. Most of the time, I am telling a story.

And stories need beginnings, middles, endings, surprise twists, rhetorical questions, good characters, quick asides, a sense of synesthesia, a resounding “so what?”, some flavor, some sentiment. You know, the stuff that makes the juice worth the squeeze. Stories need emotional resonance. If I’m not feeling it, you won’t either. So I have to feel it.

What I prioritize in this phase: close reading, concrete themes, specificity, identifying narrative beats, vetting sources, defining boundaries, emotional touchstones

What I ignore: ancillary or tertiary topics, further inputs, new video ideas, unrelated resources

Phase Three: Writing the Script

Writing is hell. I hate writing. I love writing.

I care a lot about words. I’ve said many times that I treat vocabulary in my scripts like cards in singleton formats – you get to use every word once, so make it count. I believe in this.

I also care about being specific. There is a short list of words I will never use in any of my scripts (among them “interesting” and “thing” and “incredible”) because they have been watered down by misuse or they don’t mean anything at all. Being specific produces sharper ideas, and it usually results in expanding your lexicon. Besides, I just like learning new words – “ossuary” is a cool word. So is “autostereogram,” which is the technical term for those Magic Eye illusions. Refusing generic words pushes you toward specificity.

Since my videos are narrated, I write to the sound of the spoken word. This means I will read aloud while I write and chop away at phrases that cause verbal stumbles. Some sentences look good, but are difficult to pronounce – think of a ventriloquist avoiding plosives in their punchlines.

Writing is also, very sneakily, the second phase of research. While writing, I find myself returning to my sources to cross-check facts and verify my claims. Occasionally, this results in stumbling into new information, which creates ripple effects throughout the script. Sometimes this conflicts with a previous idea. Holding yourself accountable is an ethical responsibility in this regard. As my high school English teacher always said: “prove it!” Anything you propose as truth must be supported by your sources. If it can’t be proven, then it must be clear that you are presenting your subjective opinion on the matter.

Writing, for me, is torturous and slow. I start every morning by re-reading everything I’ve written thus far, timing myself as I go. This helps keep a good sense of pace to the script and refreshes my mind to the greater whole as I proceed. During this phase, I begin to develop a sense of authority on the subject. Teachers become experts once they teach and not a moment before. To write, they say, is to understand.

When the script feels complete, I will review it a few more times in full (often following a night of rest), make minor edits, and send it to VO.

What I prioritize: storytelling, pacing, flow, factual accuracy, word choice, details

What I ignore: The video editor in me yelling for writing so much, the eventual audience, the world

Phase Four: Recording Voiceover

Everything goes through the script.

I want this to be clear: the script dictates the video. A finalized script closes the door on new ideas and becomes an executive order, and with it, a fundamental change in my role. No longer am I swimming around untethered in the realm of possibilities – it’s time to realize the damn thing. I go from Plato to Aristotle, from architect to builder.

I have a primitive recording setup. I know nothing about sound design or audio mixing. My narration technique is poor, and my softer voice makes recording a pain. Some folks enjoy my rather monotonous delivery, but I’ve always found it dull. I’ve strongly considered taking voice acting lessons. At my last teeth cleaning, my hygienist asked me what I do for a living. “I make videos that put people to sleep,” I told her. “So you’re a hypnotist?” she responded.

I’ll take it.

A weird side effect of doing Rhystic Studies for a decade is that I’ve gotten pretty good at sight-reading from a teleprompter. Freelancing produces many surprising collateral skills that are hard to quantify on a CV. In a way, this document is a catalogue of all the strange experience I’ve gained along the way.

I need about half a day to record, edit, and export the narrated script. The finished .wav file gives me a good idea of how long the video will be, which helps me map my remaining production schedule and establish expectations for video editing.

What I prioritize: pronunciation, clear takes, breathing, a quiet time of day, a calm mind

What I ignore: fancy effects, ornamentation, technophilia, the constraints of my hardware and recording setup, qualms about my voice

Phase Five: Video Assembly and Editing

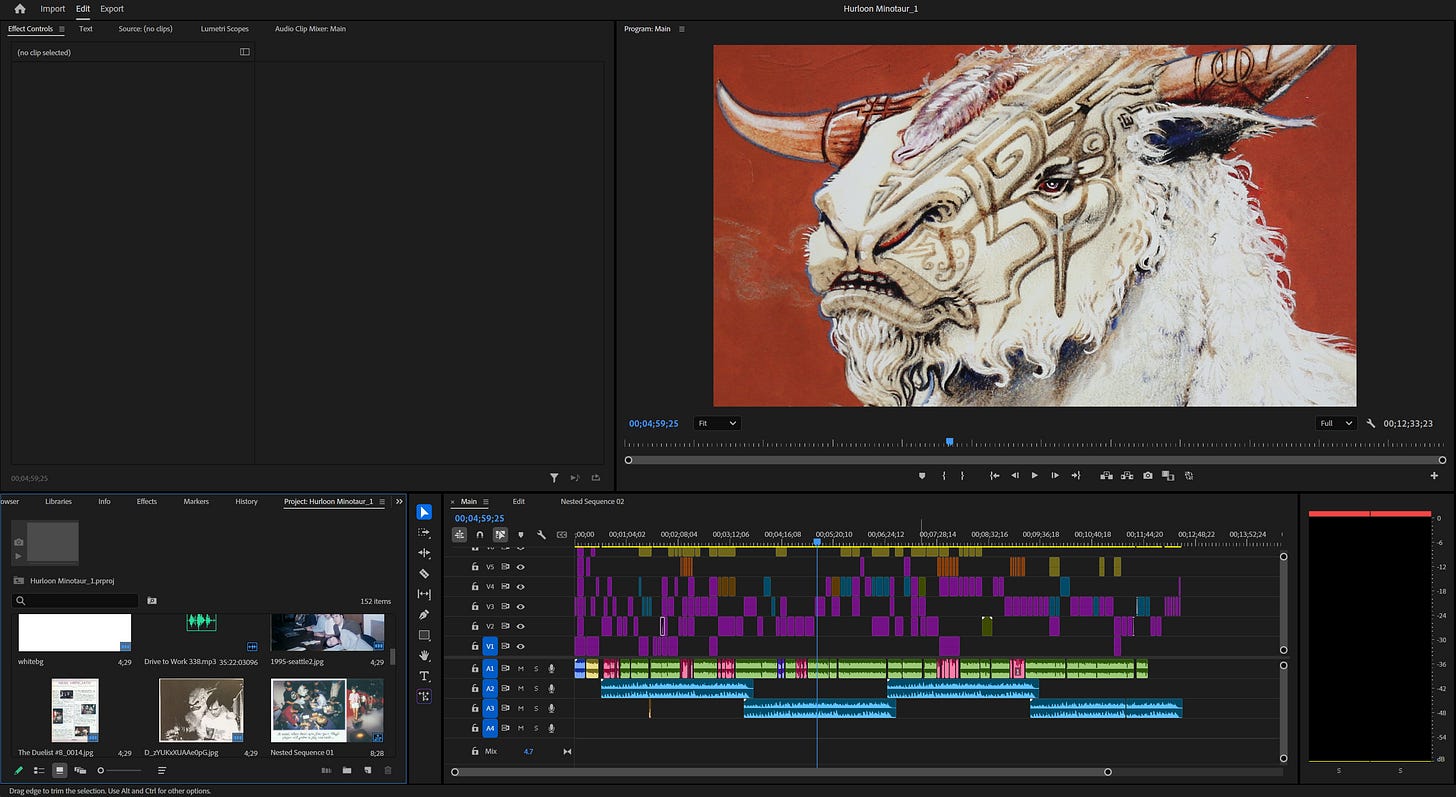

Opening a new Premiere Pro file comes with a giant sigh of semi-relief. On the one hand, the hart part is over. On the other hand, the hard part has just begun.

Video editing is an exercise in decision fatigue. There is natural overlap between Sam (the writer) and Sam (the video editor), as some sections of my script will organically suggest imagery that lends itself to video. If I’m talking about Tarmogoyf, then maybe I’ll show a photo of the card Tarmogoyf. But what if I don’t? What effect does that create? There is a lot of theory here that I will gloss over, as it extends beyond the scope of this article, but consider the differences in these three scenes that illustrate the same line of text:

What you choose to show against what you choose to tell creates affect, and affect is the most intoxicating ingredient at your disposal for visual storytelling.

Anyway.

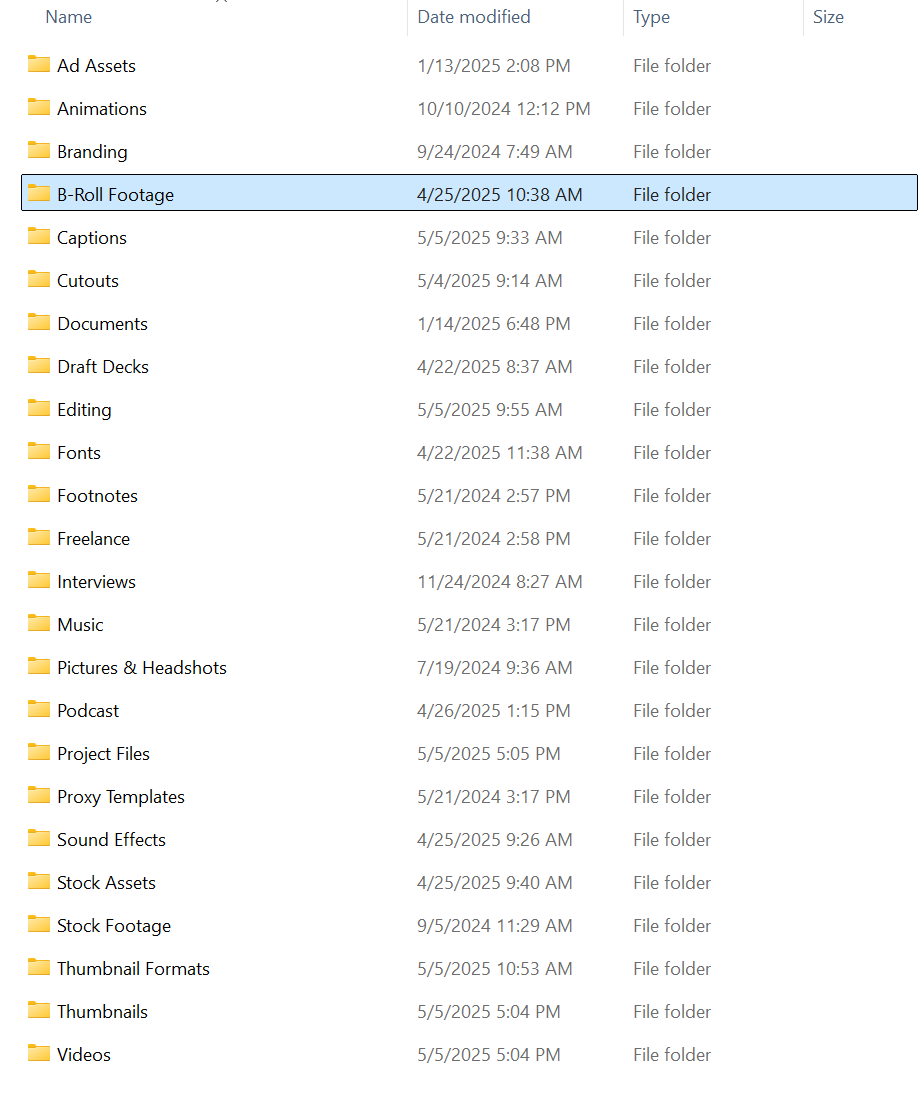

There are many, many, many invisible jobs hiding beneath the umbrella of “video editor.”

I spend an extraordinary amount of time searching for music that will fit the tone, pace, and atmosphere of my videos. I spend even longer cutting and splicing stems in Audition to match music with narration. It is never an accident how or when a track begins or ends – everything is orchestrated. With a few exceptions, I never reuse a song. This assures every video is entirely its own.

In the early years of YouTube, graphics and images in videos generally looked like shit. We were still pulling jpgs from magiccards.info and panning them over low-res scans of basic land art. I attribute some of my early success to following the general principal of “make a video that looks good.” Funnily enough, I think so many videos nowadays look good…and that’s about it. Lots of dazzling visuals and flashy animations and fancy soundstages, but take away the budgets and the set dressings, and what’s left? I suppose we’re a superficial species, after all.

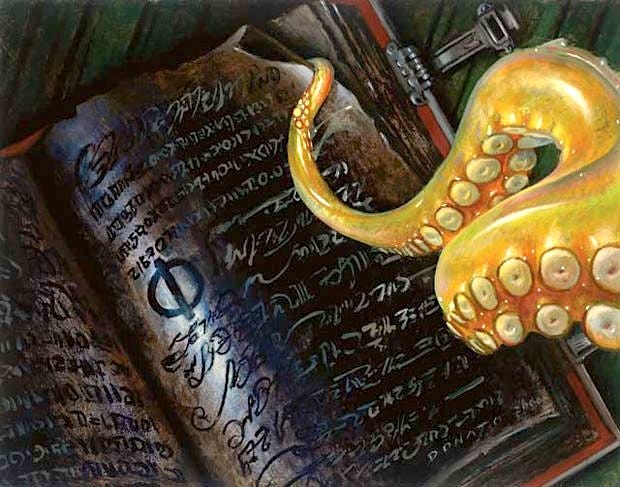

All that is to say: I still adhere to my conviction to make videos that look (relatively) good. I want my images to be clear and my graphics to be beautiful. I am particular about fonts and I screen test dozens before I am satisfied. I shoot close-up shots with my DSLR and take b-roll video with a 4k camcorder. I make new backgrounds custom to every project. I seek high-definition scans of illustrations and pull high-resolution pngs of Magic cards from Scryfall. That site remains the greatest boon to everyone working in the medium and beyond. Their impact is immeasurable.

Even after all that, my videos are pretty low to the ground – slideshows, even. Ken Burns comes up a lot when people describe my style (though, admittedly, I’ve never seen one of his documentaries.) Despite this, my videos are extremely time consuming to assemble. Getting 4 minutes of a rough cut marks a good day of editing. 10 minutes is a miracle.

I mentioned earlier that I play the guitar – I think editing video is closer to a musical skill than a mechanical one. Over time, you start to develop a deep sense of rhythm to the discipline. You start cutting to milliseconds. Moving objects in and out begins to feel like directing a theatre performance, and you’re barking at your actors to stay on cue. Certainly, you can teach the technical skills (drag keyframe to here, copy-paste a text element there), but only through doing it can you develop the craft. I edit video through my body. It’s very visceral.

Once the arduous process of montage is complete, I breathe a genuine sigh of relief and move on to the most satisfying phase of them all.

What I prioritize: clarity, pace, audio-visual harmony, building moments, setting daily goals, persistence

What I ignore: micromanaging, the third-quarter slump, burnout, uneven progress

Phase Six: Detailing and Video Review

There’s a tangible shift in my mood once I get to this point – I’m talking raging thunderstorms to meadows glistening beneath rainbows. If the writing phase is defined by irritability and agitation, and the video editing phase resembles an anti-socialite in lockdown, this phase is an early release from work on a sunny Friday afternoon. It feels like that brief wave of satisfaction that overcomes Sisyphus while he’s watching the boulder roll down the hill.

By now, I’ll have reviewed segments of the project about 20-30 times each, but never in full. As such, I’ll start this phase by watching the video front to back, imagining myself a first-time viewer. What do I notice most? How do I feel? Do I get bored? Am I smiling? Does this make my mind race? Am I paying full attention? Is the time flying by?

I’ll then go through the Premiere Pro file imagining myself a stern boss who is strict about every minute detail. I’ll scrutinize the editing choices. I’ll cross-check spelling on lower thirds. I’ll be as critical as possible and point out every lazy decision that editor Sam made. “Don’t be lazy” my grandpa used to tell me, and I always hear his voice when I’m refining these jagged edges. So many minor tweaks happen at the end of a project when I hold myself accountable in this way. All of them are for the better.

I’ll then go through the Premiere Pro file imagining myself a joyful baker who spends their days decorating cakes. I’ll add sound effects and a couple fancy animations. I’ll spice up some graphics and make them a little prettier. I’ll throw in an image that makes me laugh. My anthropology professor in college reminded us on many occasions: “don’t forget to skylark.” Sometimes I lose my sense of humor in this process and I take my work too seriously. Adding these final, flowery touches allows me to let loose and embrace play.

The final, significant lift in this phase is writing closed captions. This has to be done once audio-visual is locked due to timing. It took me six hours to produce these for the recent Ornithopter video, in part because it’s terribly monotonous, and because Magic has a million weird words that automated captions screw up, and because I have a high standard for how subtitles should behave. “How you do anything is how you do everything,” as they say.

Once the video is completely finished, I send it to Media Encoder to export. I then watch it three more times, front to back, on three different platforms (my editing computer, my laptop, and my phone), checking for glitches or hiccups and observing the discrepancies between the devices. Videos look and sound totally different through these various speakers and screens, and you have to come to peace with all the artifacts and compression that accompanies them.

After I give myself the all-clear, I begin post-production.

What I prioritize: “bumping the lamp,” reflecting on the process, gesturing toward the whole, finding minor errors, accenting and trimming, adding bells and whistles

What I ignore: rushing to completion, comparing to other projects, overdoing the small stuff

Phase Seven: Post-Production and Distribution

Or, in business terms, “marketing.”

There are many ways to gamify and exploit every decision made in production, but it’s in this phase that opportunities become deeply sinister. You can conjure up heinous thumbnails with violent red arrows and o-faces. You can dupe viewers into clicking your videos with vague or alarming titles. You can manipulate SEO’s and reverse-engineer algorithms and publish when you know your audience is most vulnerable to distraction – YouTube analytics give you all sorts of data to weaponize. Perhaps that will lead to more clicks, but why make something only to present it as a bag of tricks? Are you trying to trap rats in attics?

I choose to ignore all of that, partly out of disgust toward the aesthetics, and mostly out of contempt for the moral grayness. I actually have much stronger feelings about this subject, but you can insinuate.

I understand that I work in an attention economy that is becoming increasingly more predatory. But I am not cynical about my audience. I want to give them a gift – that’s my side of the bargain. The single most important factor that drives every decision behind Rhystic Studies is this: will you be happy to have spent your time here? That’s it. More than anything else, I value your time. I want nothing more than to reward your time.

So all of my decisions in “marketing” funnel through that standard.

Every video needs a description. Most important to me is the first line in the dropbox, which summarizes the whole project. I aim for a single sentence abstract. This often becomes the “copy” that will accompany posts on all my platforms. Beneath that are categories bullet-pointed by emojis of key information. At the moment, these details are: my sponsors, my websites, my guests, the featured music, the video chapters, and a link to the full script. None of this is “necessary” per se, but I want this section to be clean, organized, and useful. Once again, it serves the social contract between myself and my audience.

The anatomy of a Rhystic Studies thumbnail has some obvious recurring motifs. They all tend to have big text, some isolated card art, a monochromatic background, and maybe a gentle frame. Nonetheless, they take me at least four, sit-down sessions to build; there are so many micro-decisions involved in producing such a simple image.

Many of my video titles resemble every essay and journal article I read in grad school that leverage what we affectionately call the “academic colon.” That is, you get to be a little creative and a little poetic before the colon, but after the colon, buddy, you need to tell me what your paper is actually about. Instead of colons, I use dividing bars because I like the way they look.

Navigating the YouTube backend also takes time and some know-how, but it’s mostly on rails and full of self-explanatory checkpoints. These include: uploading SRT files for closed captions, unchecking a million boxes so the platform doesn’t automate your videos to death, submitting monetization verification that nobody in your video is being beheaded or whatever, formatting the links that appear as “cards” during the video and as buttons at the end, disclosing sponsorships, placing and removing ad breaks, setting visibility, adding licenses, calibrating comment moderation, yada yada yada.

With a thumbnail ready and a short description written, I start distributing. Lately, I’ve embraced the infrastructure of scheduling everything beforehand. I’ll synchronize the video to release simultaneously with posts on all my socials. I’ll upload the written script and format it on Substack, which also includes a link to the corresponding video and a section with all my sources. This is purely a service I provide for those who would rather read than watch. I also add the video to my depository on my website – you never know where or how someone will find you. Coordinated visibility can be achieved without being noisy. I certainly want people to know that I’ve made something new, but I don’t want to be obnoxious.

Once the video goes live, an overwhelming sense of dread washes over me. I can’t explain this one. It’s like those dreams you have when it’s opening night of the play, but you haven’t rehearsed or memorized any of your lines, and sometimes you’re up there on stage with your bare ass out. After publishing, I want to throw up. I want nothing more than to be completely invisible. All the excitement that motivated me from the kindling of phase one through the drudgery of phase seven instantly transforms into misery. I mean, I really hate this part.

Once I’m done with a project – actually done – I want nothing to do with it anymore. It completely evaporates from my mind and my mental cache. I won’t watch the video again for months, sometimes years, sometimes at all. In a certain sense, it becomes yours. It goes on to take shape in the strange aether of the World Wide Web, and it illuminates a hundred thousand screens somewhere far, far away, and my voice begins speaking softly into a microphone, weeks and weeks of my life condensed into twenty-two minute snippets of images panning slowly over gentle soundtracks, and you will know part of me, but I might never, ever know anything about you.

Just wanna say, your commitment to not wasting your viewers' time really shines through your work. I've always felt that your content is a cut above most out there online, even outside of the mtg space.

Thank you I'm gonna copy this entire process to make something about Godzilla.