The Rules Text is Irrelevant

On Magic’s aggressive shift toward premium collectibility

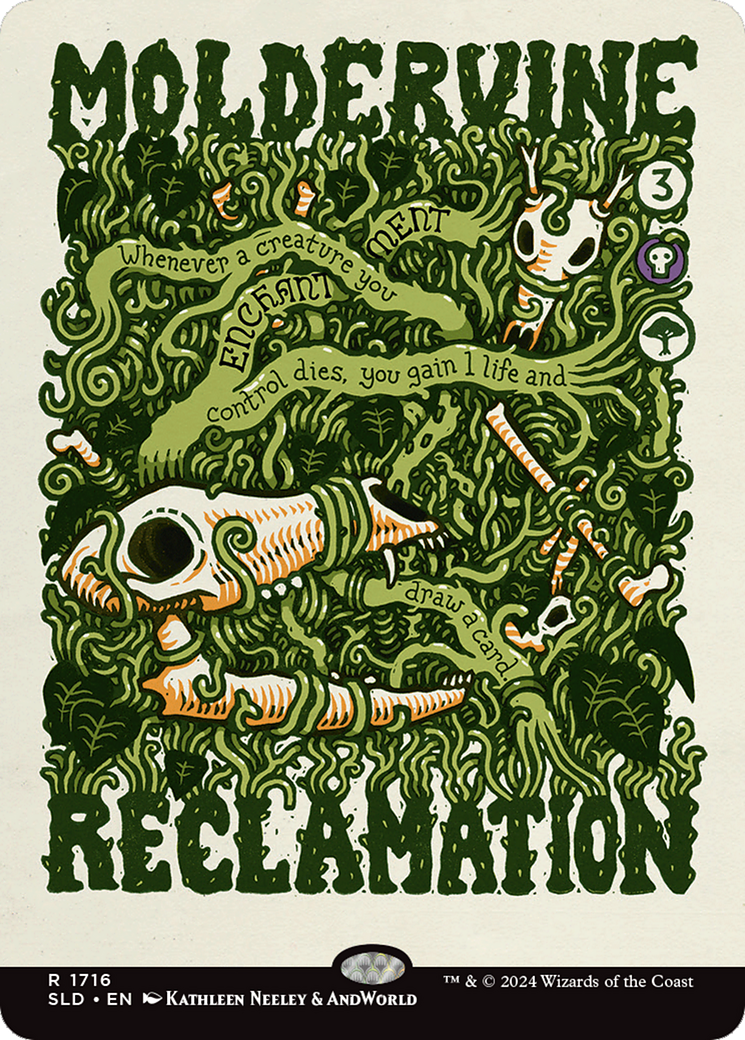

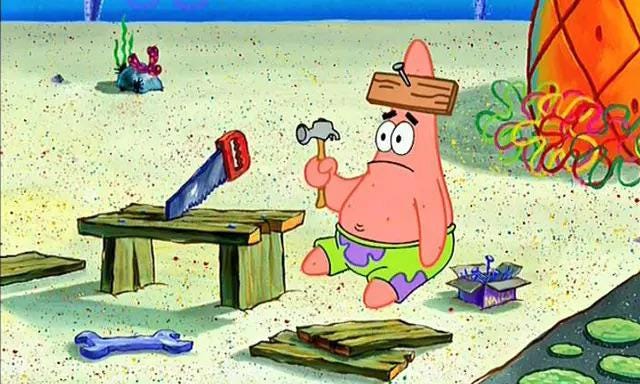

A few months ago, Magic’s offshoot arthouse project et experimental reprint factory Secret Lair produced a small batch of cards in collaboration with Nickelodeon’s SpongeBob SquarePants. The cards sold well, predictably so, despite a generally unfavorable review of the choices for their in-universe equivalents, despite the unfriendly direct-to-customer distribution model that requires waiting in hours-long queues without guarantee of access to purchase, and despite the elevated price tag derived from an artificially limited print run. They sold well because SpongeBob was on a Magic card, plainly so, and because some of them were memes. Among the collection was Barktooth Warbeard, an over-costed legendary creature with no abilities first seen in Legends (1994) reskinned as Patrick Star nailing a 2x4 to his forehead.

I find the implications of this card riveting. It is a portent of a fast-approaching future in which the rules text of our game pieces may no longer matter. Or, to be more precise, a future in which sales are not dependent on mechanical novelty, but on cultural capital.

The overarching question that drives this essay is this: can you sell a Magic card that has no rules text?

The Rules Text is Invisible

A few years back, Wizards of the Coast printed Omnath, Locus of Creation as a full-art, textless promo for game stores to distribute as prizes for their Store Championships. Omnath, Locus of Creation is a notoriously wordy card, and so the textless version was clearly done as a bit.

Magic has tried this gag a few times before to notable effect. Grinders from the mid aughts will remember Damnation, Lightning Bolt, and Terminate, but Cryptic Command is the example that comes quickest to mind. The former trio were repurposed as sleek versions of cards with relatively simple effects that everyone had memorized; Cryptic Command was the exception. Players occasionally misremembered Cryptic Command’s four modes, even with access to the normal printing, and often at the expense of a game loss in a high-stakes tournament.

The cultural capital of a textless Cryptic Command was cultivated in-house. Its value was sown from a decade of appearances at Pro Tours and the provision of attractive eternal formats filtered through a stable infrastructure of organized play. We made the textless Cryptic Command a collectible, and it was our inside joke. Nobody outside of Magic could ever understand what this meant, or why it made us laugh.

You can sell this card without rules text, but only to Magic players of a certain ilk.

The Rules Text is Illegible

A considerable slice of Secret Lair’s offerings can be best described as “stylishly ungrokkable.”

I fully endorse this approach. The brand has positioned itself as unconventional and intentionally transgressive against traditional design rules, especially for trading cards that require certain visual attributes to be functional as game pieces. The fact that so many Secret Lair cards don’t look like Magic cards is the point, and a huge notch toward their appeal. These are meant for display in the trophy case that is your fancy binder.

The Amonkhet Invocations toed this line back in 2017 and exposed a violent nerve in the player base that shook the creative team away from experimenting with premium cardboard for a while thereafter. I’ll never forget the vitriol that Forsythe had to field. I mean people got livid. These were shocking in a time when, two years prior, gamers were queasy at the sight of the bulky black border anchoring the bottom of the new M15 frames. I remember wrinkling my nose at the Invocations at first glance, but within a year, they had become my favorite of the Masterpiece series by a considerable margin. Funny how things grow on you.

You can sell cards with illegible rules text as long as they’re a) intentionally positioned toward collectors and b) backed by “normal” equivalents to cross-check for rules discrepancies. One could argue they don’t even have to look good (see: the extensive aforementioned SL catalog), but I wouldn’t make that case. I think Secret Lair is conceptually awesome.

The Rules Text is Obsolete

Here’s where the rubber meets the road, so to speak.

There’s a hypothetical world in which the power level of any given Universes Beyond set was intentionally designed to be equivalent to that of an outdated Core Set. Imagine if the Nazgûl from Tales of Middle Earth was functionally Hypnotic Specter plus a value or two in the power/toughness box. On the one hand, you isolate a massive audience of deeply enfranchised Magic players who want to play with their favorite characters from The Lord of the Rings in their bracket 3 EDH decks. On the other hand, the new Magic players (who you are ostensibly trying to attract and transform into diehards with precisely this product) get to learn the game the same way we all did: with simple cards and easy-to-parse effects.

The problem is that bad Magic cards sell poorly. Or do they?

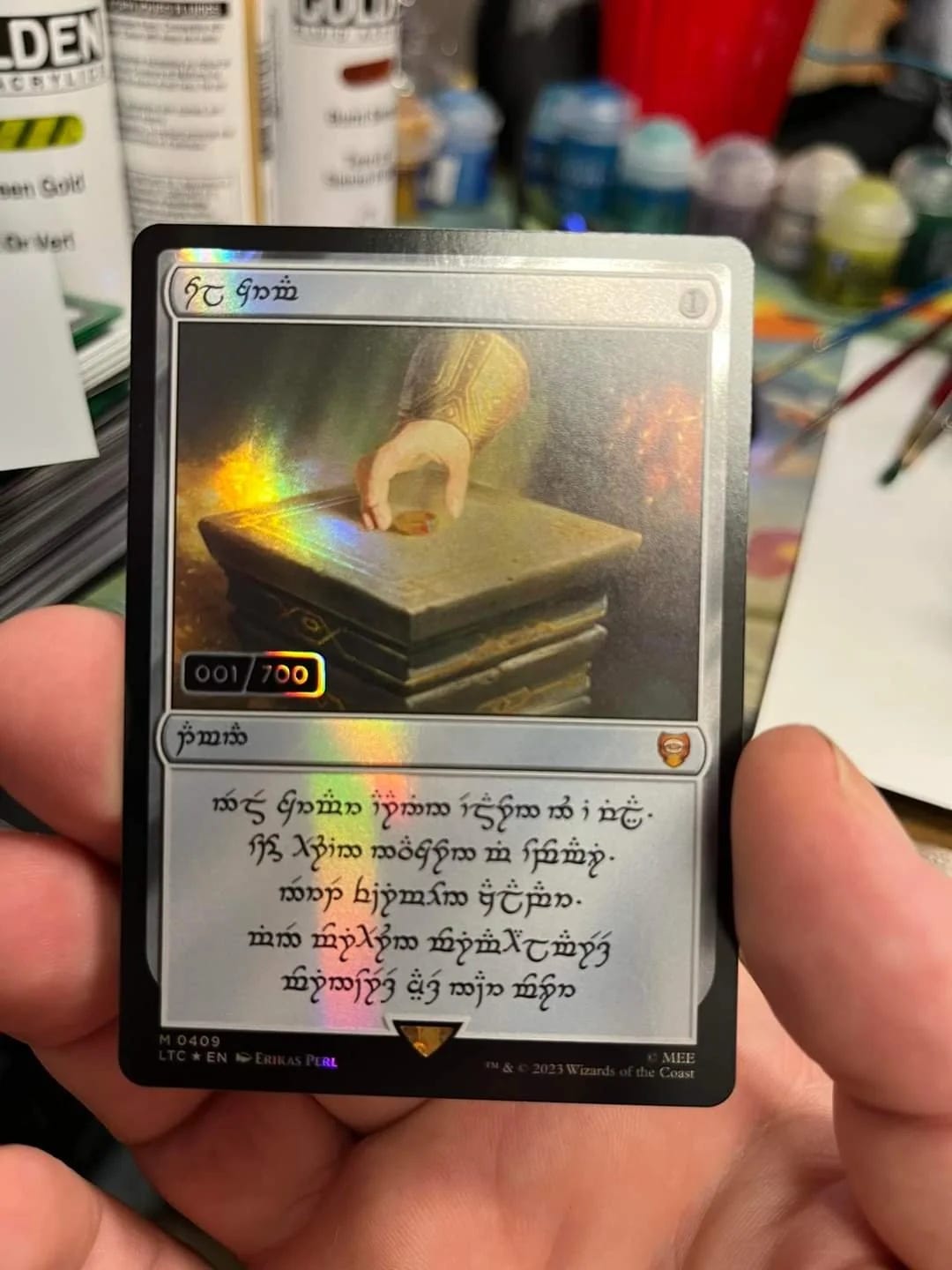

For now, the answer is yes: the number of people who buy cards and play the game is higher than the number of people who buy cards just to look at them. The One Ring (unserialized) was made a powerful Magic card to reflect its weight in the narrative. It had legitimate play applications, both casually and competitively, plus the convenient upside of being a cool collectible you could show to your friends and family who recognized the name “Elijah Wood.” The One Ring sold tons and tons of booster boxes, and the 1-of-1 The One Ring introduced the reality that Willy Wonka was no longer just a fictional character in a chapter book for children.

Here’s the thing: we don’t yet have a large enough sample of Magic cards that suck mechanically but sell extraordinarily. But we’re getting closer.

The Rules Text is Irrelevant

Like many American kids in the burgeoning consumerist market of the 1990’s, I was obsessed with Pokémon. I played the Game Boy Color games, I watched the anime, I collected the cards, I begged to eat at Burger King (horrific) just to acquire the cross-promotional peripherals. I could not tell you what Charizard “does” – then or now – but my admiration for the holographic 1st edition copy sitting in my binder remains as potent today as when I was 8 years old. I mean I really love my Pokémon cards, but I will never, ever play with them.

Magic (the game) will continue to matter to the subset of people who know the rules and engage in its complicated systems. Actively materializing adjacent to this legacy group is a much, much larger mass of people who will never, ever be bothered to learn what their cards “do” – that Tifa has “abilities” detailed in written words beneath the rendered image of her flexing at the camera is so far outside of their peripheral vision it may be actually invisible.

Final Fantasy became the highest selling Magic set in the game’s 32-year history before it was available to the greater public. This is unprecedented. Magic has never been collectible to anyone on the outside. Never. It has certainly nurtured the collector archetype throughout its tenure, but always from within, as the “player-collector” (see: Masterpieces, Cryptic Command, The Reserved List.) Tales of Middle Earth’s stats were significantly padded by the rabid hunt for the 001/001 Ring. There were other chase cards in the set, including serialized versions of the remaining rings of power, but I don’t believe those moved the needle. Hell, I forgot they existed until I sat down to write this article.

Final Fantasy is not The Lord of the Rings. Its fanbase is so much greater, so much more in-tune with participating in a hobby-subculture and so much better preconditioned to purchase collectibles – toys, art prints, games, manga, the works. We’re speaking about magnitudes of difference here. It would be nice if even a percentage of these players learned how to play Magic, but the rules text simply does not matter at the checkout counter for this crossover. Their Cloud Strife is my Charizard. They may never see another set symbol beyond that little Chocobo.

You can sell a record-breaking number of cards with powerful rules text, but only if you acknowledge that the illustration is the one closing the deal.

The Rules Text Beyond

What scares me most about Final Fantasy’s success is not that Hasbro’s risk to repurpose Magic has paid off. They now have the runway to become bolder in marketing the UB concept to other suitable franchises, and Magic’s own worldbuilding may be slowly nudged further and further onto the back-burner to make room. That’s just big business. Besides, Magic players seemingly love the Final Fantasy set. It’s hard to make the claim that “this product is not for you” when everyone has been celebrating this release for a month straight (and spending tons of money on it.) I’ve never been happier to be wrong about this concept because of the joy it has brought to countless players (and to the development team, who deserve praises and raises galore.)

Actually alarming to me is the price people are willing to pay for the set’s most premium cards.

It seemed asinine that a booster box of Magic’s 30th Anniversary edition was pitched at $1,000, but finding a Collector Booster Box of Final Fantasy for that low a price would be considered a steal. Golden Chocobos are this year’s The One Ring, but I don’t think the same level of stat-padding is involved here. People are just rabid for these cards. We’re entering a Turbo Man era of buyer frenzy, and it’s only the middle of the summer.

I’m pretty suspicious about hype cycles and consumer culture writ large. I don’t think it’s sustainable, or to be frank, healthy for anyone to be spending thousands of dollars on randomized packs of cards, regardless of speculation about their long-term value. The financial upside remains unproven – do you think the serialized elvish Sol Ring would sell for $13,000 today, divorced from the context of the hyper-moment that marketing instills? More immediately, the walk-away content of any given Collector Booster is tenuous at best – some killer, mostly filler, in my experience. I’m not here to cast my judgment, but it just doesn’t feel good to see friends and colleagues fall into these kinds of traps. Sports betting is becoming more and more entwined with the viewership ecosystem by the day, and the statistics aren’t showing good returns for participants (monetarily, psychologically, socially…) I guess it just comes back to Sullivan’s timeless tweet:

To be candid, I wish UB took a few steps back on complexity. I talked myself into the idea of a curious newbie entering the game with as few mechanical hurdles as possible, especially if the likes of Spider-Man and SpongeBob attract a relatively younger audience. Just as well, I’ve made peace with Hasbro’s decisions to push Magic into the greater geeks-and-games market. Ultimately, the numbers are undeniable, even if they’re bolstered by millions of folks buying cards from outside our little niche. I hope some of those people learn to play the game. I hope we don’t forget, in this grand discussion of company mascots and market projections and billion-dollar brands, that Magic is the best game ever made. I hope we can keep the rules text relevant, even when it’s not the point of sale.

imma be real this is how I found out that chocobo isn’t a pokemon

This is a dark road we're on.

If we look at the track record: assurances from WOTC that UB and Secret Lairs were just a top tier premium "add-on" to magic, and it wouldn't disrupt formats, that they were just a fraction of available product, and we could just engage with the classic product line and ignore what we don't like... that Magic would remain Magic.... well, it was misleading when they said it, it isn't true now, and trends seem to indicate it'll be even less true in the future.

we are now facing a future where half of magic is ALREADY universes beyond, and powerful cards in those sets and products make the UB branded cards ubiquitous and unavoidable. What was once a joke about how bad it could get is already in our rear-view mirror, and the dark road stretches on.

every new UB release compounds the problem, and I think MARVEL sets over the next two years are going to skyrocket us over the border into a new era in Magic where we won't even recognize it at all anymore. When we get there, I think we'll see these sale trends begin to reverse, as the longstanding fanbase of the game steadily lose interest and stop playing, and the new players with their mechanically broken cards featuring franchises from across multimedia produce a play environment that will feel over-commercialized, and ultimately... unfun to play.

Maybe a decade from now, someone at WOTC will revive core magic, and a new generation will get a crack at playing MTG... but for now, we're in a full nosedive regardless of what the sales figures may say.